Bias Types in ML Pipeline#

Bias, in technical terms, refers to a deviation from the “standard” and is crucial for identifying patterns in data that fuel classification and generation algorithms. To evaluate problematic or harmful biases in algorithms, the entire development process—including modeling, training, and usage—should be assessed from a cross-disciplinary perspective [Ferrer et al., 2021].

Bias exists in many forms. The Oxford CEBM’s Catalogue of Bias identifies over 100 types of biases in medical literature, occurring across various phases of system design, such as conceptualization, selection, and even the reporting phase.

A significant challenge in bias identification is the lack of a unified language for defining biases. Researchers from different fields often use different terms for the same systemic errors. Recent efforts, such as NIST’s publication and initiatives by ISO and IEEE working groups, aim to standardize bias definitions. However, capturing nuanced changes across specific use cases and categorizing them into an ontology for cross-domain mapping remains a complex task. Here, we summarised potential bias sources and types found in data, algorithmic design, and human use/interaction aligned to our risk management and assessment workflow (see Chapter Continuous Safety Monitoring). The chapter does not present an exhaustive list of bias types, but explains how we used the existing guidances (Oxford’s catalogue, Turing Commons, NIST SP1270, International AI Safety Report-2025) in our fairness evaluation and risk management workflow.

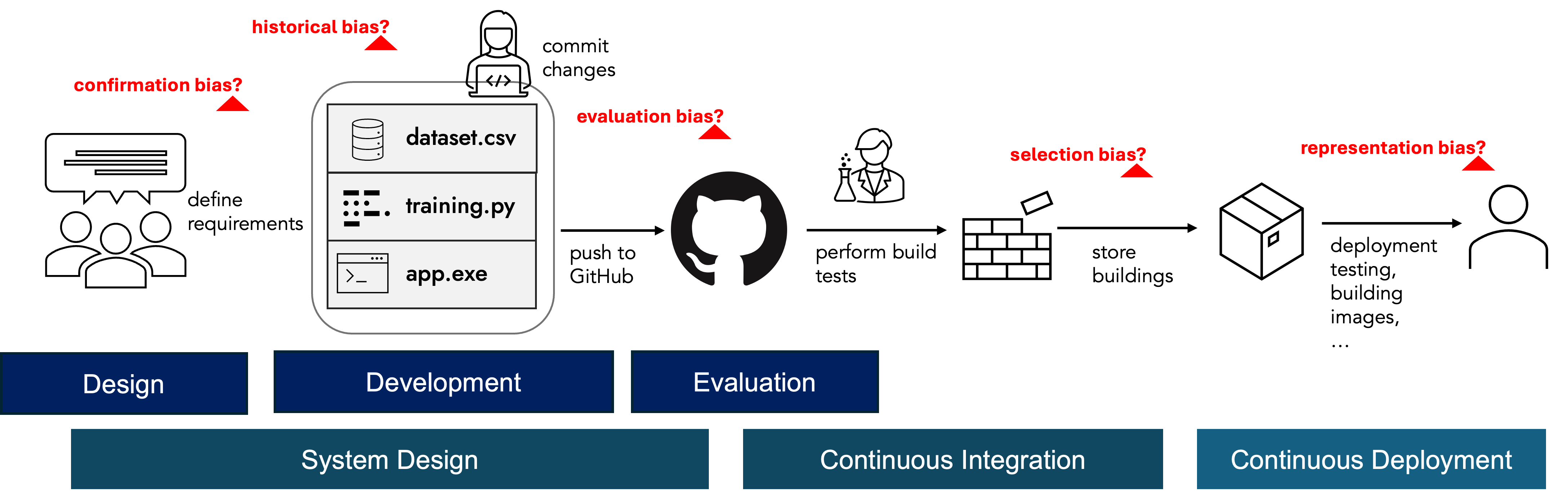

The below timeline demonstrates bias sources with the corresponding most likely ML stages. The bias list is obtained from the recent International AI Safety Report:

Bias in the Data#

This section mappes these biases (and more) to NIST’s Bias Taxonomy (Towards a Standard for Identifying and Managing Bias in Artificial Intelligence).

NIST: Statistical Bias > Selection and Sampling#

Measurement bias: The bias in the data might stem from errors or inconsistencies in how data is collected, measured, or stored. While measurement bias can affect data generally, it may disproportionately impact certain groups. A type of sampling bias is “bias in the tail”. When we train our models using large datasets, there is a risk of prioritizing accuracy/fairness on the data-rich head of the distribution. In this case, we forgot the tail of the distribution, which can potentially have a large impact in the bias.

Representation/Sample Bias: Even after reducing the impact of historical bias, representation bias can occur when the data is misaligned with the real-life state. This bias occurs when the data used to train an AI is not representative of the population it’s meant to serve. For instance, an insurance algorithm trained on a dataset primarily composed of claimants from a particular region might inappropriately inflate premiums for individuals from that area. Another example is when a facial recognition system is primarily trained on images of light-skinned individuals, it may perform poorly on darker-skinned individuals. Ensuring diverse and representative training data is crucial for reducing this type of bias. So, it is essential to ask which communities will be affected after deploying our solution.

Bias in Feature Selection: Bias can also be introduced during the feature selection process, where certain features might be chosen or discarded in a way that introduces or exacerbates bias. This can be intentional or unintentional. For example, excluding features that are correlated with protected attributes might reduce apparent bias but also remove valuable context that could lead to better decision-making. Transparent and careful feature selection processes are necessary to balance fairness and performance.

NIST: Systemic Bias > Historical#

This bias arises from past societal inequalities or prejudices reflected in historical data. For example, if residents in a specific area historically experienced higher loan default rates, an algorithm trained on this data might unfairly penalize loan applicants from that area. This bias can be perpetuated in a feedback loop, where biased outcomes further reinforce the bias in subsequent data iterations. Addressing historical bias requires not only debiasing techniques but also critical examination of the data sources (distribution) and the societal context (contacting with all stakeholders) in which they were generated.

NIST: Statistical Bias > Processing and Validation#

Proxy bias occurs when seemingly neutral variables used in an algorithm correlate with sensitive attributes. Even when protected characteristics are excluded from the data, using proxy variables like geographic location, which might be correlated with ethnicity, can lead to discriminatory outcomes. Intersectional bias refers to the compounded disadvantage that individuals may face when they belong to multiple marginalized groups. For example, an algorithm might be biased against women of color in a way that is not evident when examining gender or race in isolation. Addressing intersectional bias requires a nuanced approach that considers the interactions between multiple protected attributes.

NIST: Statistical Bias > Use and Interpretation#

Emergent Bias: This bias arises after an algorithm is deployed due to shifts in societal values, knowledge, or population dynamics. The COVID-19 pandemic provides a relevant example. Algorithms relying on income data must now account for factors like furlough payments, while insurance algorithms need to adapt to changing risk profiles associated with different occupations. Failing to adjust for these emergent biases can lead to unfair outcomes, potentially favoring those least impacted by societal changes.

Feedback loop bias: happens when the output of a biased model influences the future data that is collected, creating a cycle of increasing bias. For example, if a predictive policing algorithm disproportionately targets certain neighborhoods based on biased historical data, it will lead to more arrests in those areas, further reinforcing the initial bias. Breaking this cycle requires intervention strategies that monitor and adjust for bias continuously.

NIST: Human Bias > Individual#

Bias in Data Labeling: Bias can be introduced during the data labeling process, where human annotators may bring their own prejudices and biases into the labels they assign. This is particularly problematic in tasks requiring subjective judgments, such as sentiment analysis or facial emotion recognition. Ensuring diverse and unbiased labeling practices, along with regular audits, can help mitigate this issue.

Bias in the Algorithmic Design#

NIST: Statistical Bias > Processing and Validation#

Objective Bias: This bias stems from the algorithm’s primary goal. An algorithm focused on maximizing the overall accuracy of credit default predictions might achieve high overall accuracy but still exhibit bias by being more accurate for certain groups, disadvantaging others.

Evaluation Bias: Evaluation bias arises when the metrics and benchmarks used to assess model performance do not adequately capture fairness or bias. Standard accuracy metrics might not reflect disparate impacts on different demographic groups. Consequently, models might appear to perform well overall while still being biased. Developing and using fairness-aware evaluation metrics is essential to identify and mitigate this issue.

Weighting Bias: In algorithms, different features are assigned weights to indicate their importance in predicting the outcome. If these weights are not carefully calibrated, it can introduce bias. For example, an auto insurance algorithm that heavily weights credit scores over driving records might result in customers with good credit scores but poor driving records paying less than those with excellent driving records but lower credit scores, even if their overall risk is statistically similar.

NIST: Statistical Bias > Use and Interpretation#

Algorithmic Transparency and Interpretability: A major challenge in addressing bias is the lack of transparency and interpretability in many machine learning models, especially complex ones like deep learning networks. Without understanding how decisions are made, it is difficult to identify and correct sources of bias. Developing methods for explaining model decisions and making algorithms more interpretable can help stakeholders trust and verify the fairness of the models.

Bias in Human Use and Interaction: As AI systems often learn from data labeled or generated by humans, they can inherit and amplify existing conscious or unconscious biases. If an algorithm learns from insurance underwriters’ decisions, it might perpetuate those underwriters’ biases, regardless of whether they are intentional. We further addresses these challenges in our finance use case: Human-System Interaction View on Fairness

NIST: Human Bias > Group#

Sunk Cost Fallacy: It is a cognitive bias where people continue investing in a decision, project, or activity based on the time, money, or effort they’ve already spent, rather than on its current value or future benefits. This happens even if the rational choice would be to cut losses and stop. For example, staying in a failing project because you’ve already spent a lot on it, even though continuing adds no value, reflects the sunk cost fallacy.

NIST: Human Bias > Individual#

Availability Bias: This bias is a mental shortcut where people judge the likelihood of an event based on how easily examples of it come to mind. If something is more available, memorable or recent, we tend to think it’s more common or likely, even if that’s not the case. For example, after hearing about a plane crash on the news, someone might overestimate the risk of flying, even though air travel is statistically very safe.

Bias and Mitigation Cards#

A useful activity for mapping bias together with diverse stakeholders is using a set of cards as conversation starters. The Bias and Mitigation Cards, developed by the Turing Commons project, outlines various types of biases that can arise throughout the lifecycle of an AI project. It categorizes biases into social, statistical, and cognitive types. Each bias is described with prompts to encourage careful consideration of its possible presence within the project. Furthermore, the cards suggests potential mitigation techniques and useful prompts to have a fruitful conversation.

The categories of biases and their types are:

Social Biases: Historical Bias, Representation Bias, Label Bias, Annotation Bias, Chronological Bias, Selection Bias, Implementation Bias, Status Quo Bias, De-Agentification Bias, Missing Data Bias

Statistical Biases: Measurement Bias, Wrong Sample Size Bias, Aggregation Bias, Evaluation Bias, Confounding, Training-Serving Skew

Cognitive Biases: Confirmation Bias, Self-Assessment Bias, Availability Bias, Naïve Realism, Law of the Instrument (Maslow’s Hammer), Optimism Bias, Decision-Automation Bias, Automation-Distrust Bias

Download the cards: alan-turing-institute/turing-commons

Useful Resources#

Bias and Discrimination in AI: A Cross-Disciplinary Perspective [Ferrer et al., 2021]

KPMG, Algorithmic Bias and Financial Services: A Report prepared for Finastra International

Bias in AI Course by the Alan Turing Institute: alan-turing-institute/bias-in-AI-course

Bias Self-Assessment Chapter of Turing Commons: https://alan-turing-institute.github.io/turing-commons/skills-tracks/aeg/chapter4/bias/