AI Safety Assurance#

The quest for fair and responsible data and model development is crucial for ensuring overall AI safety. In 2023, the UK government organized an international summit to address AI risks and discuss coordinated mitigation strategies. One significant outcome of this summit is the Bletchley Declaration, which emphasizes understanding AI risks within “the context of a wider global approach to understanding the impact of AI in our societies.”

AI assurance is the process of evaluating and assuring expected properties of AI systems throughout their lifecycle. It involves techniques like verification, validation, and safety analysis to ensure AI systems operate ethically, accurately, and consistently. Throughout the AI-enabled system development process, assuring safety requires two main stages:

In the first stage, during the requirements planning phase, an interdisciplinary team establishes trustworthiness goals by conducting a comprehensive risk management process and formulating specific arguments.

In the second stage, the team use the evaluation and mitigation techniques as evidences of the safety claims and gathers information from existing transparency artefacts, such as model, data, and use case documentation.

Building Arguments#

See Trustworthy and Ethical Assurance Platform for a detailed view of building arguments for assurance. You can use the platform to create your AI safety arguments.

An argument-based approach to assurance aims to demonstrate the rationale behind decisions or actions taken regarding a system through a structured argumentation process that demonstrates how arguments about a system’s goals are justified by evidence. This process results in the creation of an assurance case, a document that sets out the argument for the system’s trustworthiness.

The main components of an assurance case are:

Goal Claim: This claim directs the focus of the assurance case towards a desired value or principle of the system. For example, a goal claim could be that an AI system is “explainable”. The goal claim should be specific and clearly defined to avoid ambiguity.

Context: Context elements define the specific conditions under which the arguments are being made. For example, the context of an AI system used by healthcare professionals in a hospital would be different from an AI system used by patients at home. Making the context explicit helps in evaluating the validity of the arguments and the sufficiency of the evidence.

Property Arguments: These are lower-level arguments that specify the properties of the system or project that contribute to achieving the goal claim. For example, property arguments for an “explainable” AI system could include the techniques used to interpret the model’s outcomes or whether users can contest decisions based on the explanations provided.

Strategy: This element outlines the reasoning and approach used to develop the argument supporting the goal claim. Strategies help break down the argument into sub-arguments, making it easier to understand and evaluate.

Evidence: This is the foundation of the assurance case and provides the basis for trusting the validity of the arguments. Evidence can include empirical data, expert opinions, or adherence to technical standards. The type of evidence required will depend on the specific arguments being made.

Practical Suggestions for Building Arguments#

Create goals around trustworthiness characteristics, and relevant legal and regulatory requirements. For example, a development team in the EU area, can use NIST’s AI RMF and EU AI Act as a starting point.

The context can be structured with the business, design, and user research teams. User researchers can inform about the considerations around AI-enabled, and rule-based solutions.

Creating the property arguments is the most challenging step of this process. It requires developers and other stakeholders to discuss the possible issues and mitigation approaches. So, each team member should conduct a comprehensive literature review and adapt the existing guidelines and techniques to their use case. So, we created a hierarchical mechanism to structurally create these properties. The strategy consists of four main levels: (1) ML Stages, (2) Components, (3) Assessment, and (4) Implications. See Continuous Safety Monitoring chapter.

We suggest developing strategies while creating properties actively similar to defining abstract objects throughout the software engineering.

Once the properties are structured, the team should decide what kind of evidences they need to collect, and how they can collect it efficiently and continuously. Automating this process, can help them to define pass-fail type tests throughout building the model.

Collecting Evidences#

Throughout the development of ML models, developers and other stakeholders use various documentation formats to enhance reproducibility and communicate the details of artefacts with both internal and external stakeholders. Organizations use metadata recording formats, such as model cards, data cards, and algorithmic transparency frameworks to improve transparency across development and deployment workflows. We refer to these documentation tools as “transparency artefacts,” which are designed to enhance clarity, accountability, and trust in ML systems.

We can use these transparency artefacts as justified evidence to verify the team took the required actions and created enough evidence for the given arguments. The key requirement for this kind of evidence is they must be grounded in measurable and reproducible outcomes such as benchmarking results, auditing trails, or red teaming reports.

Check our Evidence Collection Guide to learn more about using transparency artefacts in your codebase.

Choosing Metrics#

When presenting the evidence for the given argument, clarity in metrics is critical. Metrics provide the foundation for assessing whether a system meets its objectives. However defining meaningful metrics is not always straightforward—much like the evolution of time measurement.

Throughout history, measuring time has been a challenge. Ancient civilizations relied on natural indicators like the sun’s position or water clocks. Over centuries, we developed more precise methods, from mechanical clocks to atomic timekeeping. Today’s system of hours, minutes, and seconds is widely accepted and highly reliable. However, even with this standardized system, nuances exist when we define notions and metrics that depend on this measurement system. For instance, “being late” is a notion. However, the metric for “lateness” is subjective and context-dependent.

Take a meeting scheduled at 15:00. If you arrive at 15:01, you are technically late. But context matters. In a formal office setting, one minute may be significant. However, for a casual meeting with a friend outdoors, a 15-minute delay might still be acceptable. By applying a buffer threshold—3 minutes in an office, 15 minutes for a social meeting—you create a nuanced metric for lateness.

The key takeaway: a robust measurement system provides the basis, but practical application depends on context and thresholds.

We now face a similar challenge in defining assurance metrics for trustworthy AI systems. Just as time measurement requires global consensus and refinement, developing clear, context-specific metrics for AI is essential. These metrics must account for performance, fairness, safety, and transparency across various scenarios.

For example, the existing benchmarks for fairness evaluation do not take context into account. The benchmarks can be descriptive, normative, and correlation-based. However, they might not be directly transferable to the real-life use case to evaluate the fairness of the AI system. Wang et al. (2025) [Wang et al., 2025] present a new benchmark suite (DiffAware) to evaluate a model’s ability to appropriately treat groups differently (difference awareness) and to differentiate only when necessary (contextual awareness).

Effective assurance relies on clear, context-aware metrics. History shows us that standardizing measurements takes time and effort, but it’s essential for consistency and trust. As we work toward standardizing assurance metrics for AI, the lessons from measuring time remind us of the importance of clarity, flexibility, and precision.

Choosing the Benchmark#

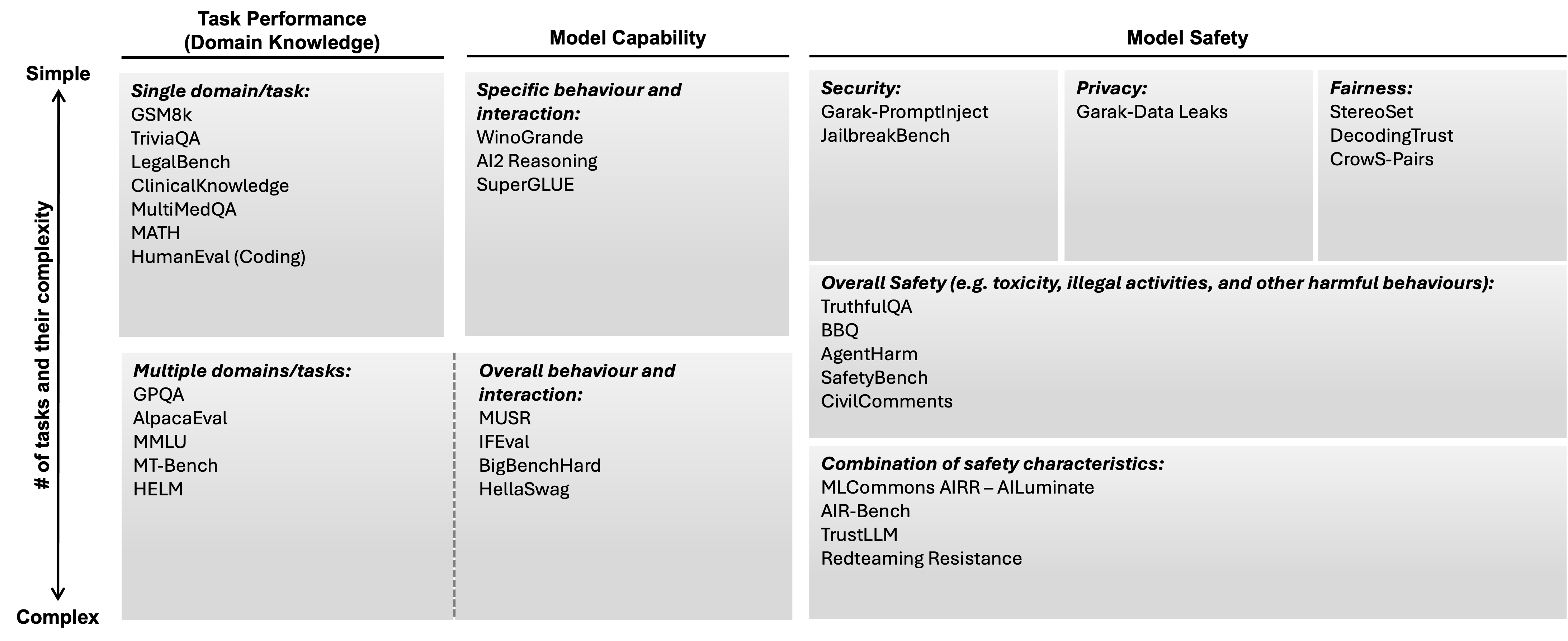

Although all data-driven algorithms require a robust and reliable benchmark, current discussion centred around benchmarks for LLMs and other general-purpose AI models.

The diagram above illustrates one way of categorising current evals for LLMs. Practitioners focus on model capability, domain-specific task performance and model safety. Model capability evaluation focuses on general language understanding such as question answering quality, reasoning, factual recall, and commonsense. Task performance can include multiple domain-specific evals such as math, coding, law, medical, and financial capabilities. Safety evaluations aims to minimise the potential harms such as toxicity and bias and adhere to ethical principles.

See AISI’s Inspect AI Evals: https://inspect.ai-safety-institute.org.uk/evals/. It provides a curated list of ready-to-use evals for LLM safety, capability, and performance assessment.

See IBM’s Tiny Benchmarks: https://huggingface.co/tinyBenchmarks. The collection includes tiny versions of selected evals to reduce the cost of benchmarking while preserving reliability.

Use Cases#

The UK’s DSIT regularly releases enterprise-level AI assurance use cases. Two examples from the financial services sector are as follows:

Case 1 - Clear Bank: Clear Bank focuses on integrating LLM (Limited License Model). They ensure fairness by consistently involving human oversight, including domain experts for continuous review and implementing feedback mechanisms to detect biases at every pipeline stage. (Link to platform page)

Case 2 - Credo AI Governance: Credo Reinsurance’s case centers on their machine learning operations (MLOps) system. Their Credo AI system automatically identifies biases in models pre-deployment. The platform evaluates fairness outcomes against established standards. However, due to compliance with anti-discrimination regulations (e.g., NYC’s LL-144), they can only compile necessary data quarterly, not in real-time. (Link to platform page)

See more use cases in DSIT - AI Assurance Use Cases.