Evaluating and Mitigating Fairness in Financial Services: A Human-AI Interaction Perspective#

The finance sector is in a constant effort to provide robust and reliable products for customers. With the rapid progress in capabilities of large language models (LLMs), finance sector started transforming some of the critical services such as enhancing customer engagement, producing financial insights, and optimizing investment activities. However, the adoption of these advanced technologies brings fairness considerations as well as security, privacy and in general, trustworthiness.

This article explores utilising the existing best practices and guidelines from Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) domain to evaluate and mitigate fairness in the system interaction level. We investigate two user interfaces and their interaction in the end-user level to discuss how HCI principles applied in these applications and what can be improved.

The Role of LLMs in Financial Services#

Aligned with our previous report, we focus on four financial service categories:

Public Communication and Customer Engagement: LLMs can significantly improve customer service by providing timely and accurate responses to inquiries. Their human-like response generation capabilities can enhance user experience through personalized communication. Further, these models can handle a vast array of customer interactions and memorise old interactions and relational information to create complex personalised experiences.

Financial Service Safety: The application of LLMs in detecting and preventing fraud is particularly promising. By analysing large datasets and identifying patterns, these models can help financial institutions develop safer products and conduct more thorough risk assessments.

Financial Insight Generation: LLMs can generate valuable insights by processing market data, producing comprehensive reports, and offering personal investment advice. These insights can inform business finance decisions, optimise market surveillance, and aid in the generation of aggregate financial reports.

Financing and Investment Activities: Investment banking, treasury optimization, private equity, venture capital, and asset allocation can benefit from improved data analysis and predictive modelling capabilities.

Examples from Human-Financial Service Interaction#

While integrating “intelligent” mechanisms, each scenario requires a unique analysis of the interaction. In this article, we focus on two scenarios: Using LLMs in (1) asset management in the context of robo-advisors and (2) generating sentiment signals for market analysis.

Sentiment Signals for Market Analysis#

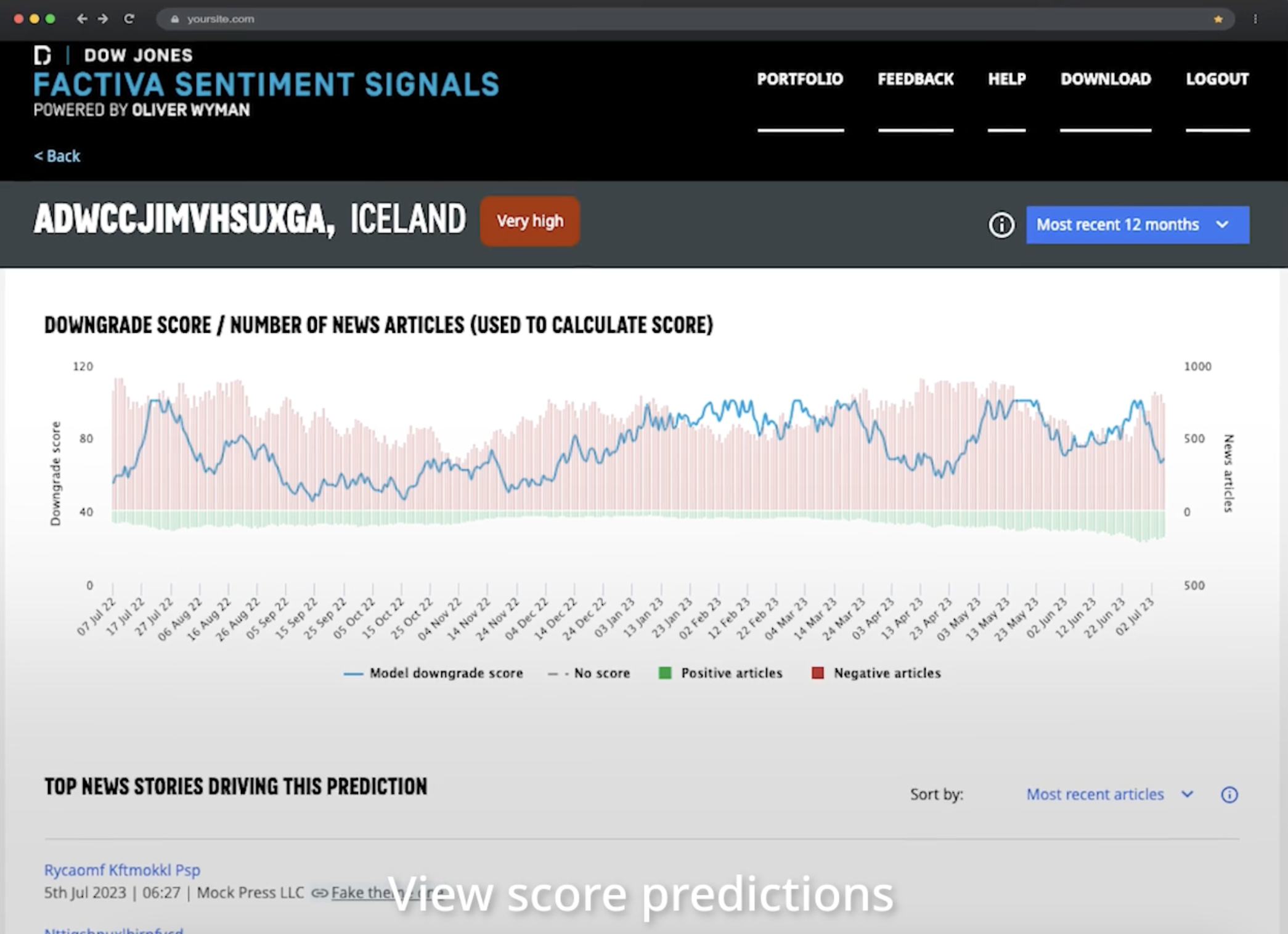

Figure is from Dow Jones

Figure is from Dow Jones

The above figure illustrates a sentiment signal analysis interface introduced by Dow Jones. In this interface, we mainly see scores from two ML models: (1) A binary (positive-negative) document sentiment classifier, (2) Downgrade scorer based on sentiment signals. They also provide top documents that impacted the decision of the models most. These news documents support a level of human-in-the-loop approach and transparency.

The steps behind the scenes:

These systems gather data from multiple sources such as social media news articles, financial reports, blogs, forums, and other relevant platforms.

Then, they pre-process the text (tokenization, stemming, and lemmatization) to break down the text into manageable pieces.

After, sentiment signal classification algorithms can categorise text as positive, negative, or neutral. They can either (1) use predefined dictionaries of positive and negative words. (2) train models on labelled datasets to predict sentiment.

Generally, most signal providers use an ensemble approach to aggregate the sentiment scores from different sources to generate an overall sentiment signal.

We can validate the sentiment signals by backtesting against historical market data to ensure they provide reliable predictions.

After the model is ready, the system should present actionable insights based on the sentiment signals. This might involve setting thresholds to determine strong positive or negative sentiments that could indicate potential market movements. We shared one example interface that presents these sentiment signals to users.

Robo-advisor for Personal Asset Management#

Broadly, these applications use:

Traditional rule-based algorithms for asset allocation, diversification, and rebalancing.

Use machine learning for personalized recommendations, anomaly detection, and improving predictive accuracy.

And, potentially, integrate sentiment analysis for market sentiment-driven investment strategies.

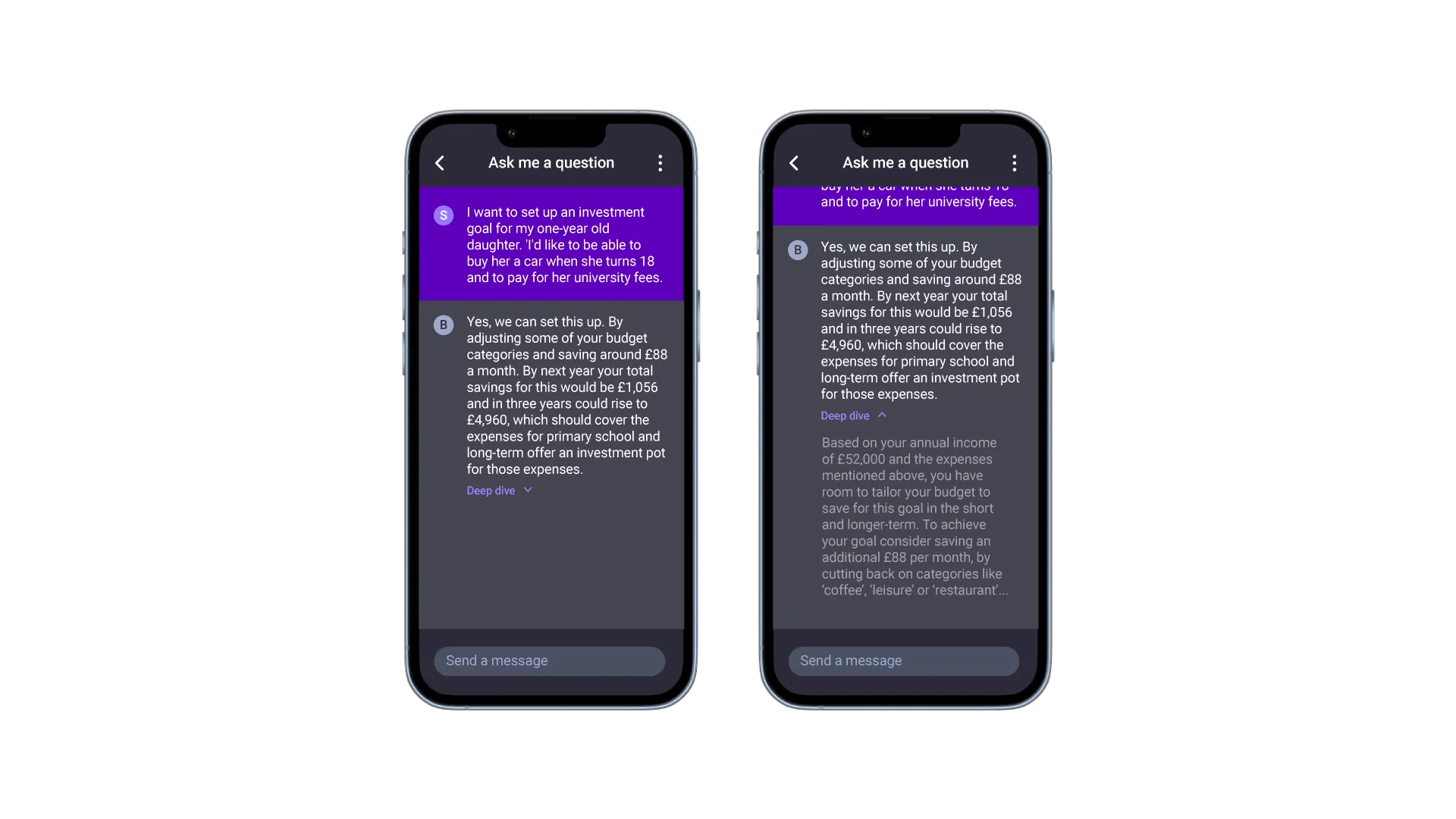

Figures are from Kin+Carta

Figures are from Kin+Carta

With the increasing availability of human-like language generation capabilities, these applications have been integrating chat interfaces as seen in the above figure. Chat interfaces provide a familiar space for novice users, which accelerates the adoption pace significantly as we witnessed in ChatGPT example. With the integration of a conversational AI can assist users in understanding their portfolio, making investment decisions, and resolving queries by asking questions in plain language. This conversational approach potentially make the interaction more intuitive and accessible, especially for novice investors.

However, integration of a chat interface also brings lots of ambiguity as the user can define queries in limited detail and system can generate an answer with assumptions. So, it brings risks of misunderstanding.

To reduce the risks coming with conversational agent integration, designers can define the system affordances clearly and improve clarity of system capabilities can reduce this risk. Clearly communicating how data (both user and market) is collected, processed and interpretd can help users to intuitively understand the decisions behind the system.

Standards and Guidelines#

Following the standards and guidelines, practitioners can structure their design processes to achieve a proactive “by design” fairness. In this document we refer ISO 9241 standards and some of the industry guidelines such as Microsoft Human-AI Interaction Guidelines and Google People+AI Guide.

ISO 9241#

ISO 9241-210:2019 is a key international standard that provides guidelines for human-centered design (HCD) processes in interactive systems. It outlines principles and activities to ensure that products, systems, and services are designed with a focus on the users, their needs, and the overall user experience. The standards focus on the overall design process evaluation rather than the system usability evaluation.

We can summarise the key concepts of ISO 9241-210:2019 as following:

Understanding and specifying the context of use: It’s essential to understand who the users are, what they want to achieve, and the environment in which the product will be used.

Specifying user requirements: Design requirements should be derived from a thorough understanding of users’ needs, tasks, and goals.

Iterative design solutions: Solutions should be developed iteratively, with users involved in each stage of the design process.

Evaluating designs: Continuous testing and evaluation should be carried out to ensure that the product meets user needs.

Involving Users: Users should be actively involved throughout the design process to ensure the end product is useful, usable, and acceptable.

Multidisciplinary Teams: The standard encourages collaboration between professionals from various disciplines, such as designers, developers, marketers, and usability experts, to create a well-rounded product.

Note

You can use ISO 9241 Compliance Checklist to check whether your design and development process follow a human-centred approach.

The figure above illustrates the recommended development process as outlined by the standards document. A crucial step in this process is the evaluation phase, where designers determine the specific improvements needed for the product. The standard emphasizes three types of evaluation: (1) User-Based Testing, where users interact with prototypes of varying fidelity; (2) Inspection-Based Evaluation, where experts assess usability and other aspects using checklists; and (3) Long-Term Monitoring, which involves identifying issues during real-world use.

In this article, we focus on inspection-based evaluation, exploring how to design this process so that practitioners can adopt an expert’s perspective and continuously evaluate the system throughout its development. One guideline we can use as a checklist in this process is Microsoft’s Guideline for Human-AI Interaction.

Microsoft Human-AI Interaction Guideline#

“Guidelines for Human-AI Interaction” outlines a set of 18 design guidelines for developing AI-enabled systems. These guidelines aim to help designers and developers create AI systems that users can understand, trust, and interact with effectively. The framework covers various stages of interaction, including initial interactions (e.g., making clear what the system can do), ongoing interactions (e.g., showing contextually relevant information), and dealing with errors or misunderstandings (e.g., supporting efficient correction). The document also includes a systematic validation of these guidelines through testing with design practitioners and AI products.

Here are the 18 guideline items from this framework:

Initial Interaction (First-Time Use)

Make Clear What the System Can Do: Help users understand what the AI system is capable of.

Make Clear How Well the System Can Do: Enable users to understand the system’s performance limits.

Time Services Based on Context: Deliver information or services when the user needs them.

Show Contextually Relevant Information: Present information that is relevant to the user’s current task or context.

During Interaction (Ongoing Use)

Adapt to User’s Experience: Tailor the system’s behavior based on the user’s level of experience.

Show Contextually Relevant Information: Continue to provide information that is relevant in the current context.

Support Efficient Invocation: Allow users to efficiently invoke the system’s functionality.

Support Efficient Correction: Enable users to correct system errors easily.

Support Efficient Dismissal: Allow users to dismiss or ignore information or suggestions that are not relevant.

Support User Control: Give users control over the system’s actions and behaviors.

When Things Go Wrong (Handling Errors)

Notify Users About Changes: Inform users when the system updates or changes its state.

Support Efficient Correction: Allow users to correct errors efficiently (reiterated for emphasis in error situations).

Offer Explanations: Provide explanations to help users understand why the system acted a certain way.

Support Forgiveness: Allow users to undo actions or recover from mistakes.

Long-Term Use (Building Trust and Reliability)

Support Personalization: Enable the system to be personalized to fit the user’s preferences and needs.

Consider Impact of Automation Failures: Prepare users for the possibility that the system might fail.

Match Relevant Social Norms: Ensure the system’s behavior aligns with social norms relevant to the context.

Mitigate Social Bias: Avoid reinforcing or amplifying social biases in the system’s outputs.

For example, sentiment signal analysis for financial market investment decisions can be improved considering this guideline as following:

Initial Interaction (First-Time Use)

The system needs to communicate the types of sentiment signals the interface can analyse (e.g., news sentiment, social media sentiment) and how these signals are processed to inform investment decisions clearly. They can use tooltips or an interactive onboarding tutorial to explain this.

Provide information on the accuracy, reliability, and confidence levels of sentiment analysis. They could use visual indicators like confidence scores or error margins to convey this.

Deliver real-time sentiment analysis and alerts during market hours or when significant market events occur. Allow users to customize alerts based on their specific interests or risk tolerance.

Display sentiment signals that are most relevant to the assets or markets the user is currently viewing or trading. For example, if the user is analyzing tech stocks, prioritize news and social media sentiment related to technology.

During Interaction (Ongoing Use)

Allow users to flag or correct sentiment analysis that they believe is inaccurate or misleading. Provide feedback mechanisms so that the system can learn from these corrections.

Provide interactive visualizations where users can explore sentiment trends over time, compare sentiment across different markets or sectors, and drill down into specific events that influenced sentiment.

Make it easy for users to quickly access sentiment analysis for any asset or market they are interested in, perhaps through a search function or quick-access buttons.

Offer global settings that allow users to adjust how sentiment signals are weighted or factored into their decision-making. For instance, they might want to increase the influence of certain data sources or exclude others.

When Things Go Wrong (Handling Errors)

Clearly communicate potential risks of relying on sentiment analysis, such as the possibility of misinterpretation of neutral news as positive or negative. Provide guidelines on how to cross-check sentiment with other data.

Long-Term Use (Building Trust and Reliability)

Ensure the interface uses professional, clear, and neutral language in its communication, suitable for financial decision-making. Avoid over-sensationalizing sentiment data to prevent irrational investment decisions.

Regularly audit the sentiment analysis models for biases that might skew investment decisions, such as biases in the sentiment data sourced from different social media platforms.

Inform users when there are updates to the sentiment analysis models, new data sources added, or changes in the analysis methodology.

Improving Fairness through Human-AI Interaction#

For both use cases, user personas can be categorized into three groups: professional investors, experienced investors, and novice investors.

Professional Investors: Certified professionals with formal training and work experience in asset management. They typically manage multiple accounts.

Experienced Investors: Individuals with significant personal experience in managing their own assets, possessing a good understanding of risks and gains.

Novice Investors: Those with limited experience and a limited understanding of potential risks and their consequences.

As financial institutions integrate LLMs (we can generalise our concerns over all kind of black-box models), we should evaluate fairness from a human-AI interaction perspective and set the first line of defence through interaction.

Fairness in this context means creating systems that are accessible, equitable, and free from bias. We can evaluate fairness across multiple layers:

Hardware and OS Layer: For example, if a demographic group predominantly lacks access to a specific device type (e.g., Android vs iOS) and your model is only deployed on one type of device, it can prevent users from accessing your model.

Back-End Layer: For example, the data sources and algorithms used in the model might inadvertently favour certain groups over others. If the data used to train the model is not representative of all user demographics, or if the model’s algorithms are not designed to account for such diversity, it can lead to biased outcomes that disadvantage underrepresented groups.

Front-End Layer: For example, the colour scheme of your visualizations can affect accessibility for users with certain vision types. If the colour contrast is not sufficient, users with colour vision deficiencies may struggle to notice important changes in their portfolio.

By addressing these layers, we can ensure that the system is fair and accessible to all users.

From Human-Centred Design to Equitable Design#

When integrating black-box models like LLMs into end-user applications, researchers and practitioners should address both technical and human-centric aspects to ensure these models operate fairly and equitably. By incorporating human-centered design approaches into our workflow, we naturally and proactively align the development process with equitable AI principles. To leverage HCI standards and guidelines for enhancing equity in our applications, we can ask a series of questions focused on different entities (data, model, system, user). Below, we have curated some key questions to guide this evaluation:

Note that these questions aim to assess these entities in the interaction level. For example, for the model entity, we can mitigate “AI decision transparency” by selecting white-box interpretable model families. However, in this article, we focus on improving transparency of the model by interaction design choices.

Users

(Persona) Who will be using the AI system (e.g., customers, employees, stakeholders)?

(Persona) What are the diverse demographics and characteristics of these users?

(Skills) How are users informed about the AI system’s capabilities, limitations, and potential biases?

(Skills) What educational resources are provided to help users understand and interact with the AI system effectively?

Model

(Transparency) Can the decisions made by the AI model be explained in a clear and understandable way?

(Transparency) What methods are in place to make the model’s decision-making process transparent to users?

(Bias) What criteria are used to define fairness in this context (e.g., equal treatment, equitable outcomes)?

(Bias) What metrics and tools are used to measure fairness and detect biases in the model?

Data

(Inclusivity) Does the system demonstrates whether training data represent the diversity of the user base adequately?

(Logging and monitoring) What strategies are employed to address and rectify any disparities found in the AI system’s decisions? How effective are these strategies in ensuring long-term fairness?

System

(Harms) What are the potential negative impacts of unfair or biased decisions on users?

(Perception) Do users perceive the AI system as fair and unbiased? How does user perception of fairness vary across different demographic groups?

(Feedback) How can users provide feedback on the AI system’s performance and fairness?

(Feedback) How is this feedback incorporated into the system’s ongoing development and improvement?

(Regulation) How does the AI system comply with relevant regulations and standards on fairness and non-discrimination?

Conclusion#

Fairness is not a one-time assessment but an ongoing process. Financial institutions should establish continuous monitoring systems to evaluate the performance of LLMs and ensure they remain fair over time. This includes regular audits, user feedback mechanisms, and updating models as new data becomes available. In this process, interpretability of the system capabilities appears as the key dynamic in the human-AI interaction. Adding interpretability elements such as highlighting word importance or saliency maps can enable users to more easily identify consistencies and ambiguities across system outputs [Thieme et al., 2020]. So, we explored the potentials and limitations of interpretability in more detail: Interpretability tools for improving fairness and equity.

Another important aspect of human-AI interaction in the financial services domain is actively thinking about involving diverse stakeholders in the development and evaluation of AI systems, especially if the system is developed for general public. This includes collaborating with regulatory bodies, customer advocacy groups, and internal teams to ensure that the AI systems align with societal values and ethical standards. We conducted an expert group meeting with different financial services stakeholders and presented the findings in

Following the standards and guidelines (e.g. ISO 9241-210:2019, Microsoft Human-AI Interaction), practitioners can inform the design process of fair finance application to ensure that the final product is equitable, accessible, and responsive to the needs of all users. Although we only focused on two checklist documents, HCI research produces many useful human-AI interaction guidelines such as Google’s People+AI Guidebook.

Training AI practitioners and developers on ethical AI principles is vital. This involves educating them on the importance of fairness, the potential impact of biases, and the methods to mitigate them. An informed team is better equipped to develop fair AI systems.

Ensuring fairness in AI is a collective responsibility that requires ongoing effort, vigilance, and a commitment to ethical principles. Through these measures, the financial sector can achieve broader intelligence and serve its diverse customer base with integrity and fairness.