Continuous Safety Monitoring#

Based on NIST’s Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework (RMF)[1]: “Risk refers to the composite measure of an event’s probability of occurring and the magnitude or degree of the consequences of the corresponding event. The impacts, or consequences, of AI systems can be positive, negative, or both and can result in opportunities or threats (Adapted from: ISO 31000:2018). When considering the negative impact of a potential event, risk is a function of (1) the negative impact, or magnitude of harm, that would arise if the circumstance or event occurs and (2) the likelihood of occurrence (Adapted from: OMB Circular A-130:2016).”

A comprehensive risk assessment requires a use-case specific vulnerability, threat and asset analysis. Although there are several risk assessment frameworks available, we can summarise these different strategies in a systematic way following a component-based strategy, as it is summarised in [2]:

Input data: Adversarial data (e.g. bias, malicious content) can exist in input,

Algorithm design: The algorithm design might assume the data and evaluation methods cover all the cases and business logic comprehensively,

Output decisions: It can be open to interpretation, or falsely interpreted,

Technical flaws: Development and testing might not be adequate to reveal the issues,

Usage flaws: In a complex business logic, interoperability issues might occur.

In this five-level taxonomy, several sub-components should be scanned against multiple factors. A scanning/monitoring solution can help researchers and practitioners to track and evaluate these critical metrics and support keeping the system safe and trustworthy.

With the rapid progress in deep learning, comprehending, evaluating, and interpreting these systems has become challenging. In this new era of advanced data-driven algorithms, AI models consist of billions of parameters and can process vast amounts of data, making it nearly impossible to ensure privacy and security assurance.

Practitioners can achieve continuous evaluation and monitoring of secure, private, and fair deep learning models through utilising monitoring tools effectively. The transparency of the results can also increase the collaboration between data scientists, developers, and domain experts by providing visibility into model monitoring results. Below, we summarised the main benefits of these tools from the security, privacy and fairness perspectives:

From a security perspective:

Tracking access to models and data, detecting any unauthorized access attempts or security breaches.

Monitoring model inputs and outputs for potential adversarial attacks or poisoning attempts.

Employing anomaly detection techniques to identify unusual behaviour in model predictions, which may indicate security threats.

From a privacy perspective:

Measuring the impact of privacy-enhancing techniques (e.g. differential privacy) to actively check individual data points cannot be extracted from the model’s outputs.

Tracking data access and ensuring compliance with privacy regulations such as GDPR or HIPAA.

Detecting any unintentional internal/external data leakage.

From the fairness perspective:

Utilizing different fairness metrics to assess the fairness of model predictions across different demographic groups or sensitive attributes.

Real-world testing (A/B like model testing) to identify and mitigate any disparities or unfairness.

Implementing state-of-the-art techniques such as adversarial debiasing or fairness-aware training quickly and evaluating their effectiveness over time.

A Structured Approach#

Creating a structured, step-by-step analysis that considers each step of the development process individually and holistically is essential for establishing an effective monitoring and risk management flow. Here, we presented a sample structure, that we use in our current development processes:

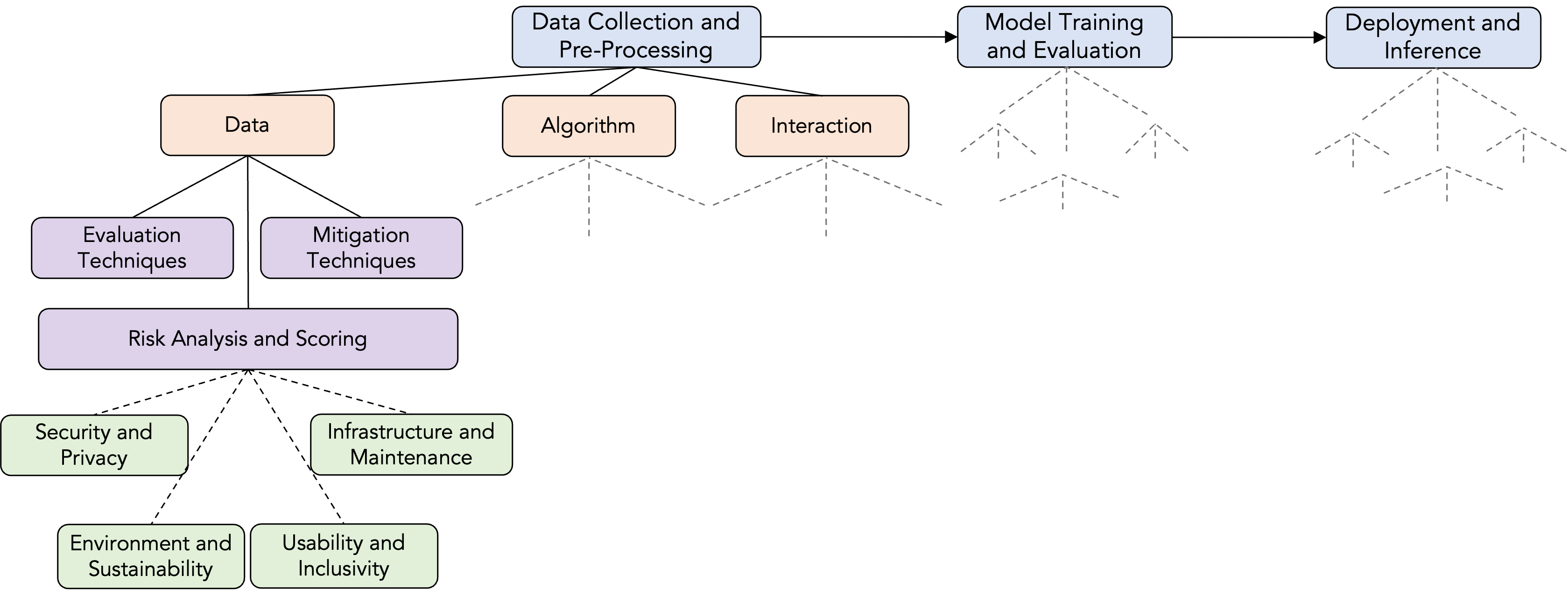

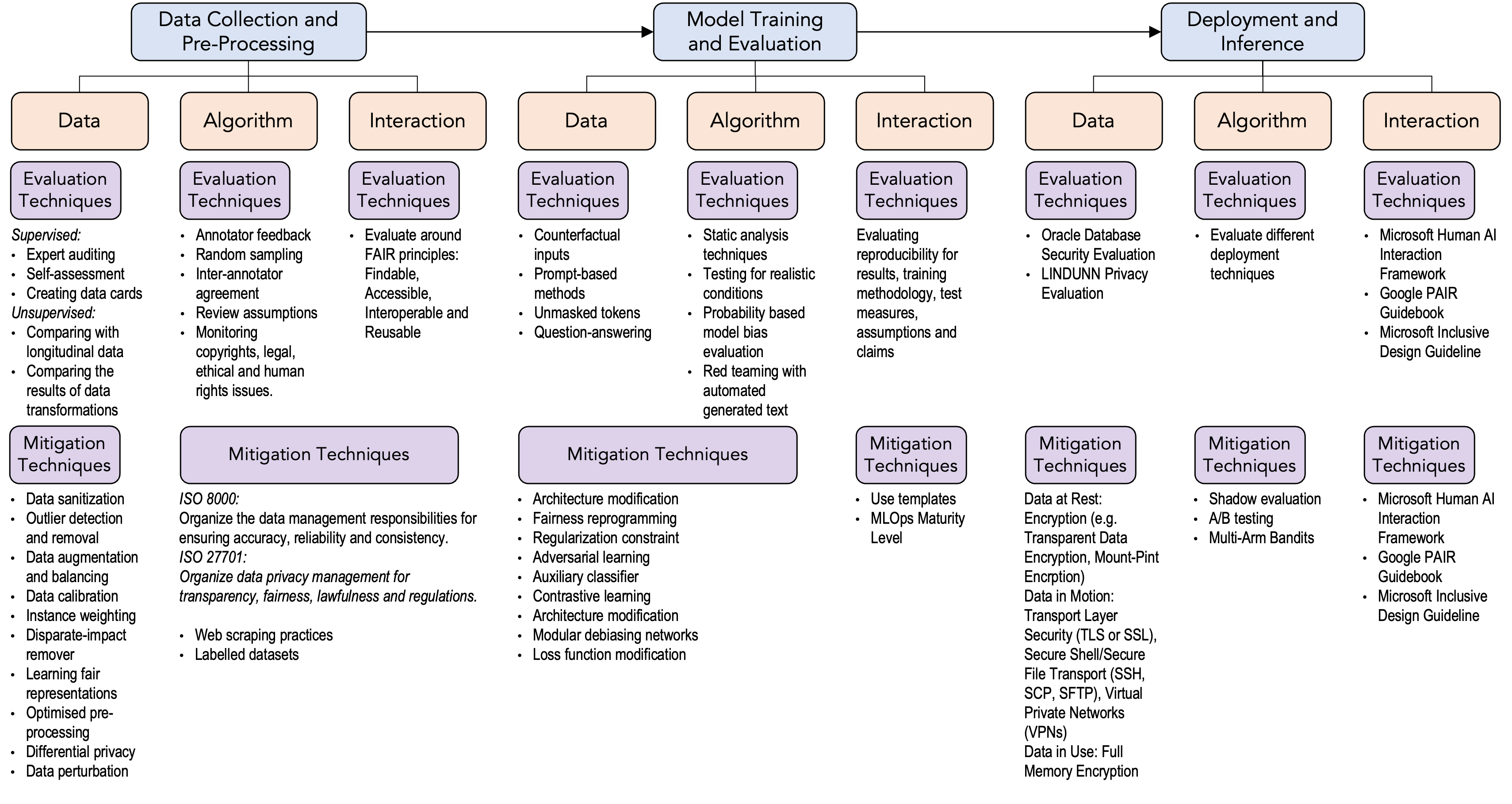

This structured framework brings existing concepts together to help researchers explore and understand a particular problem domain. In our case, we developed this conceptual framework to guide our risk taxonomy development. The framework consists of four levels: ML Steps, Components, Assessment and Implications.

ML Steps: A traditional ML pipeline includes data collection, data pre-processing, training, validation, deployment and monitoring steps. We consider three main stages in our monitoring process for simplicity.

Components: For each development stage, we should consider data, algorithm and interaction components. For each component, we also use a standardised recording format. You can see an example for fairness reporting in Chapter Fairness Reporting.

Assessment: For each component of each step, we use the selected evaluation techniques, define potential harms, rank them based on their impacts, and consider mitigation techniques. It is a similar approach to risk analysis process of the cybersecurity domain:

Evaluation: Define security, privacy and fairness, and other safety-related metrics and apply evaluation techniques based on the selected metrics.

Potential harm analysis: We followed a categorical harm analysis approach, based on AHA! and CSET-AIID harm taxonomies:

Quality of service harms

Representational harms

Legal and reputational harms

Social, societal, and well-being harms

Loss of rights or agency

Allocational harms

Mitigation: Define tangible steps to improve the model, data and interaction components based on the selected metrics.

Implications: The implications can be specific steps to be taken or generalized perspectives to consider in future iterations of the development process. Whether specific or generalized, they should lead to developing some tangible steps. We categorized implications under four headlines: “Security and privacy,” “environment and sustainability,” “usability and inclusivity,” and “infrastructure and maintenance.”

Example illustration of this structure for LLMs#

The figure below illustrates curating possible evaluation and mitigation approaches for LLMs:

In data collection and processing:

(Security) The security risks include data breaches and malicious injections. When a data breach occurs, it can potentially compromise sensitive information. Attackers might also inject poisoned data, causing biases or disrupting the model’s performance. Even if we ensure security, privacy risks might harm users. For example, aggregated data might still carry the risk of re-identification, violating privacy if proper anonymization techniques are not employed.

(Privacy) Inadequate protection of personal or sensitive data might lead to unauthorized access. These are some intended harms. The data collection, by design, can also cause direct or indirect harm through bias.

(Fairness) Biases in the collected data might perpetuate unfairness in the subsequent models, affecting certain groups disproportionately.

The next step of an ML pipeline is model training and evaluation:

(Security) Models might be vulnerable to adversarial attacks if not robustly trained, leading to misclassification.

(Privacy) Reversing the model might reveal sensitive training data. Adversaries might infer the presence of specific data in the training set.

(Fairness) Biases in the training data can perpetuate or amplify unfairness in model predictions.

The final step is deployment and inference:

(Security) Improperly secured models can be stolen or copied, posing risks to intellectual property. Models can be tampered with during deployment, affecting the output or introducing vulnerabilities.

(Privacy) Inferences made on sensitive data during deployment might lead to inadvertent information leakage. Sharing inference results with third parties might inadvertently expose sensitive information.

(Fairness) Models might perpetuate biases, leading to unfair treatment or decisions for certain groups. The ML security, privacy and fairness domains produce a vast amount of scholarly work on ML attacks and possible mitigations. Further, big tech companies, governments and NGOs publish various frameworks for secure, private and fair governance of AI. Managing these risks involves a combination of technological measures, rigorous compliance with data protection laws, ongoing monitoring, and continuous improvement in the understanding and implementation of ethical AI principles.

Limitations#

This structured approach serves to initiate the evaluation process rather than providing an all-encompassing guarantee of fairness, privacy, or security. While structured, goal-oriented methodologies are valuable, they may overlook adversarial impacts that are less obvious or require innovative approaches. This tendency is reminiscent of the “invisible gorilla” phenomenon [3], a concept originating from cognitive science.

Similarly, in the context of AI evaluation, a structured approach may inadvertently lead evaluators to overlook certain aspects, such as subtle biases or unintended consequences, especially if they are not explicitly defined in the evaluation criteria. This underscores the importance of complementing structured methodologies with a critical awareness of potential blind spots, encouraging a more holistic assessment of AI systems.

In this sense, we promote our approach as a proactive framework to detect issues, however in a red-teaming activity we suggest using a mixed of methods including creative ways to trick systems.

Useful Resources#

A well-known recent effort is Stanford’s HELM (Holistic Evaluation of Language Models): https://crfm.stanford.edu/2022/11/17/helm.html. The project, with a specific focus on transparency, measures seven metrics including accuracy, calibration, robustness, fairness, bias, toxicity, and efficiency.

Toward Trustworthy AI Development: Mechanisms for Supporting Verifiable Claims. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2004.07213#page=15.07